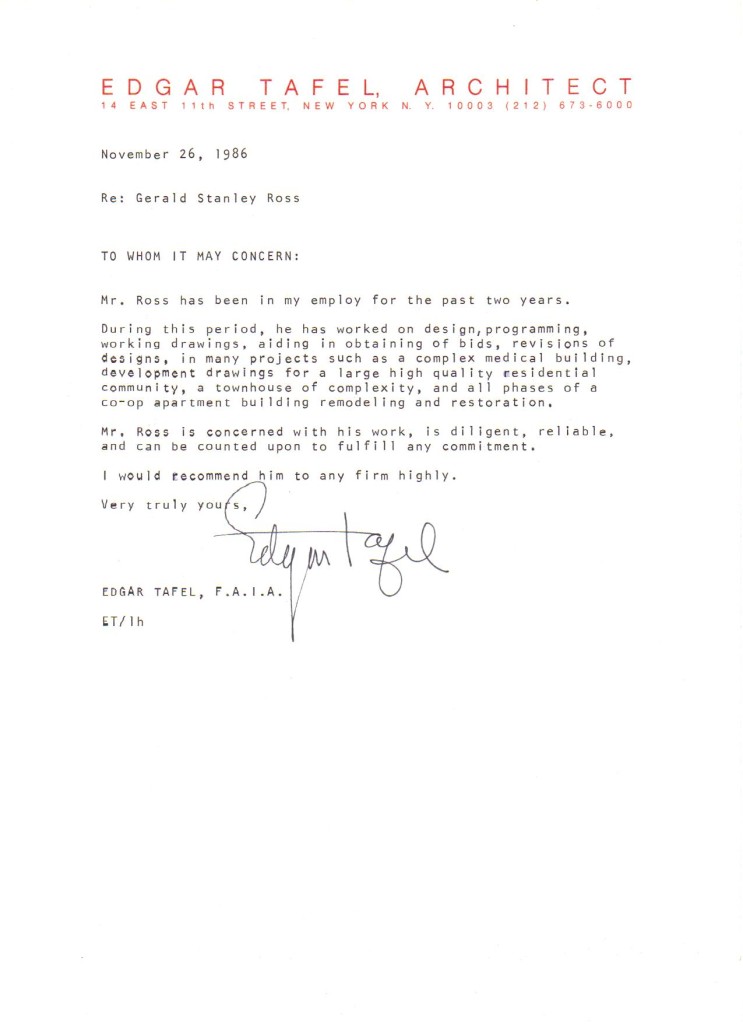

Edgar Tafel, F.A.I.A.

From the New York Times | January 24, 2011:

Edgar Tafel, an architect who was among the best known of Frank Lloyd Wright’s many apprentices, died on Jan. 18 at his home in Manhattan. He was 98.

Edgar Tafel, standing second from right, with Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin, in Spring Green, Wis., in summer 1938.

Edgar Tafel, Wright-Trained Architect, Dies at 98.

His death was announced by Robert Silman, a structural engineer who was Mr. Tafel’s legal representative. Mr. Silman said Mr. Tafel was the last surviving member of the original Taliesin Fellowship, which convened in 1932 at Wright’s home and school — known as Taliesin — near Spring Green, Wis.

On his own, Mr. Tafel designed 80 houses, 35 religious buildings and 3 college campuses, among other projects.

As an apprentice in the mid- and late-1930s, he worked on two of Wright’s most important commissions: Fallingwater, the serenely cantilevered house over the Bear Run creek in rural Pennsylvania; and the Johnson Wax Building in Racine, Wis., with its fantastic forest of mushroomlike columns. He also worked on Wingspread, the home of the company’s president, Herbert F. Johnson, near Racine.

Though apprentices were given little or no latitude to make design decisions on their own, Mr. Tafel said there was much to be learned from the master besides how to follow his orders. “Many people outside Taliesin, especially critics and writers, mistook our devotion for subservience,” he wrote In 1979. “Mr. Wright didn’t want subservience. He wanted devotion to the cause of an organic architecture — integration of form, materials indigenous to the setting, and function.”

Edgar A. Tafel was born March 12, 1912, in New York. He grew up in Manhattan, was graduated from the Walden School and attended New York University before joining the Taliesin Fellowship. His first marriage ended in divorce and his second wife died in 1951, Mr. Silman said. There were no children.

He was 20 when he arrived at Taliesin, where apprentices learned by doing: drafting, cutting stone, making plaster, preparing cement, keeping Wright’s pencils sharpened. As a pianist, Mr. Tafel was often summoned to another duty. “Edgar, go up and play some Bach for us,” Wright would command.

Mr. Tafel was an apprentice nonpareil, but he was no disciple. Tension grew between his desire to serve Wright and his wish to practice architecture himself until the summer of 1941, when he left Taliesin abruptly.

After serving in a photo intelligence unit during World War II, Mr. Tafel returned to New York and opened his own office. Perhaps his best work was a church house completed in 1960 for the First Presbyterian Church at Fifth Avenue and 12th Street in Greenwich Village.

At the peak of the glass-box movement in American architecture, Mr. Tafel took a contrarian tack — something he delighted in doing — and designed a red-brick structure wrapped in balustrades ornamented with cloverleaf-shaped Gothic quatrefoils, emulating the adjoining 19th-century church. The result was a building that fits so snugly in its context that it almost seems to disappear when glanced at across the churchyard from Fifth Avenue.

The church house might almost be called proto-postmodernist, as it anticipated by almost 20 years a more general return to traditional building forms and materials.

Other projects included St. John’s in the Village Episcopal Church on Waverly Place in Manhattan, the Protestant Chapel at Kennedy International Airport (since demolished) and the Brodie Fine Arts Building at the State University of New York at Geneseo, as well the South Village residential complex there. He planned the Fulton-Montgomery Community College in Johnstown, N.Y., and the Columbia-Greene Community College in Hudson, N.Y.

Mr. Tafel was instrumental in salvaging two interiors from Wright’s Francis W. Little House in Wayzata, Minn., before it was demolished in 1971. The living room was installed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the library at the Allentown Art Museum in Allentown, Pa.

He never turned his back on the master, with whom he maintained an amicable — if sometimes strained — relationship, until Wright’s death in 1959.

Mr. Tafel wrote “Apprentice to Genius: Years With Frank Lloyd Wright” (1979) and wrote and edited “About Wright: An Album of Recollections by Those Who Knew Frank Lloyd Wright” (1993).

In “About Wright,” he described traveling to the funeral of Wright’s widow, Olgivanna, in 1985, by recalling a visit to Taliesin West in Arizona a few years earlier: “She kissed me goodbye and said, ‘Edgar, remember, I am the only mother you have.’ ”